Likening a trip to the grocery store to shooting craps, a consumer watchdog group is reporting that data from the U.S. government shows food recalls are on an upward trend, which the advocates say could be reversed with common sense.

Overall, food recalls increased 10 percent from 2013 through 2018. Meat and poultry recalls initiated because of the potential for serious health problems skyrocketed 83 percent, according to the report from U.S. PIRG (Public Interest Research Group) Education Fund. The Philadelphia organization is not part of the U.S. government. It is an independent, non-partisan group with a mission to work for consumers and the public interest.

In the report released yesterday, PIRG officials acknowleged that advances in science and technology are likely responsible for some of the increase because they have improved detection and investigation capabilities. However, the consumer group says the research shows “serious gaps in the food safety system” during the same time period.

“The food we nourish our bodies with shouldn’t pose a serious health risk. But systemic failures mean we’re often rolling the dice when we go grocery shopping or eat out,” said PIRG’s Adam Garber in a news release about the report. “We can prevent serious health risks by using common sense protections from farm to fork.

“These recalls are a warning to everyone that something is rotten in our fields and slaughterhouses. Government agencies need to make sure that the food that reaches people’s mouths won’t make them sick.”

The PIRG report suggests several steps government and industry could take immediately to reduce the risks of recalls as well as foodborne illnesses. The organization cites as cases in point a variety of high-profile outbreaks in 2018, including a deadly E. coli outbreak linked to romaine lettuce, a widespread Salmonella outbreak traced to Kellogg’s Honey Smacks breakfast cereal, and a nationwide Salmonella outbreak traced to ground beef from a subsidiary of the world’s largest meatpacking company, JBS.

Links and chinks in the chain

The wide variety of foods implicated in those outbreaks have a common denominator, according to the PIRG report. They are all part of the “interconnectedness” of the U.S. food supply chain.

“The United States food supply chain is increasingly interconnected and disaggregated. The path from the farm to the grocery store has become increasingly complex,” the PIRG report says.

“There are separate processes for food production, distribution, processing, retailing, and preparation. Each one of those steps from farmer to consumer can also involve additional processes like aggregating, storing, and further processing food. These additional connections increase potential points of contamination and risk contamination spreading throughout large sections of our foodstuffs.”

But that complicated trek from food producers to dining room tables and lunch boxes isn’t as difficult to navigate as some industry and governmental entities contend, according to the consumer advocacy group. A couple of particularly easy first steps would be to require irrigation water to be tested for pathogens and to make it illegal to sell meat that is contaminated with Salmonella.

But that complicated trek from food producers to dining room tables and lunch boxes isn’t as difficult to navigate as some industry and governmental entities contend, according to the consumer advocacy group. A couple of particularly easy first steps would be to require irrigation water to be tested for pathogens and to make it illegal to sell meat that is contaminated with Salmonella.

“Archaic laws allow meat producers to sell contaminated products: It is currently legal to sell meat that tests positive for dangerous strains of Salmonella. A case study of the recent recall of 12 million pounds of beef sold by JBS could likely have been prevented if it this policy was changed,” the report states.

From there, the map to safer food is, in large part, just that: a map. The PIRG report calls for immediate action to make it possible to trace food back through the supply chain.

“Tracing the cause of outbreaks or identifying contaminated food in the market often takes too long, which has serious public health consequences,” the organization contends. “From identifying the cause of contamination, identifying the variety of products affected by the contamination, removing them from shelves, to notifying consumers who may have already purchased them; identifying that there was a contamination only scratches the surface of the problem.

“Transaction information can be vital to containing the public health impacts of contamination, like in the romaine lettuce case. Similarly, this information can help in identifying the cause of contamination.”

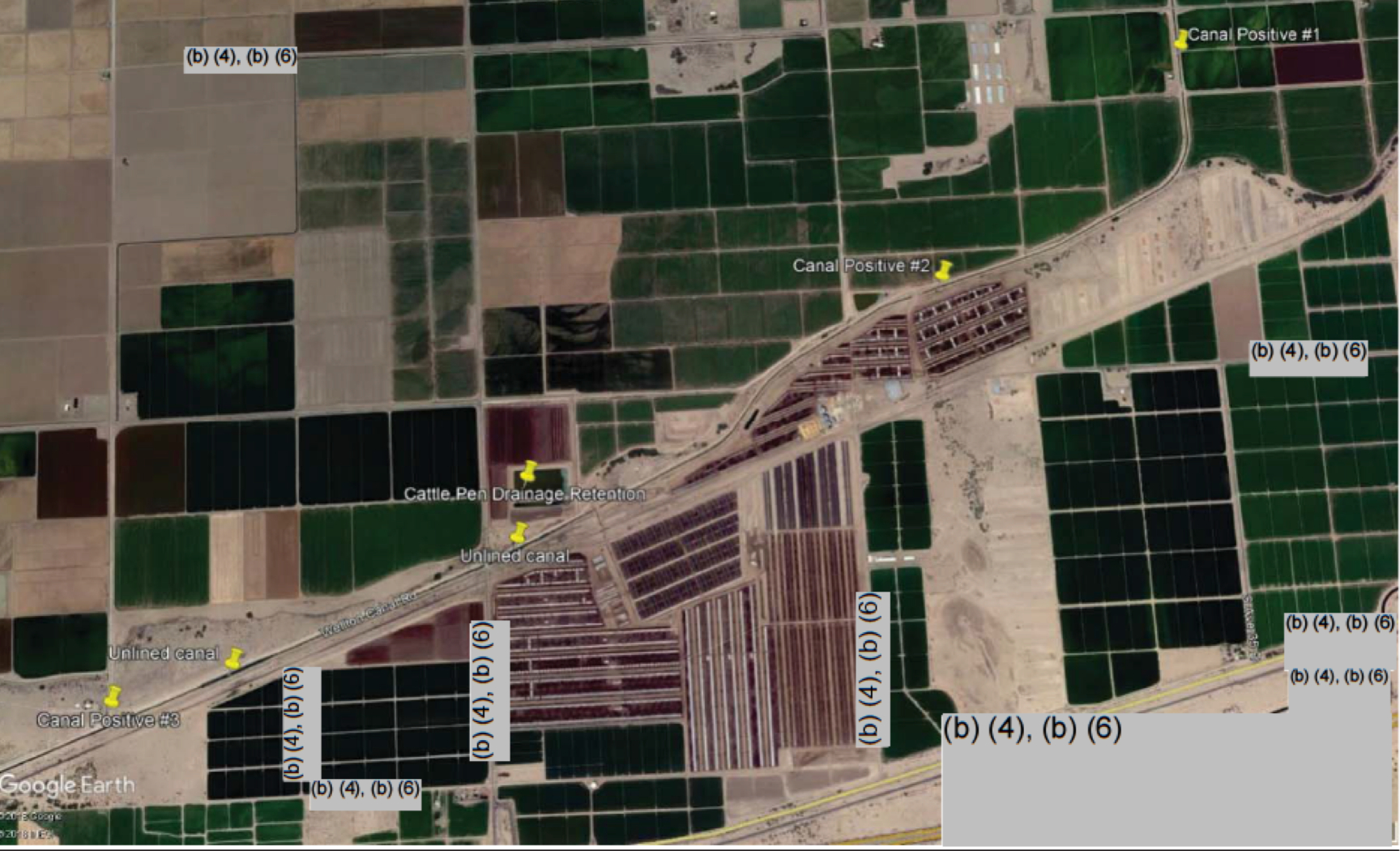

Traceability problems have plagued outbreak investigators for years, but the 2018 E. coli outbreak linked to romaine lettuce from the Yuma, AZ, growing area brought it into the brightest of spotlights. As people were becoming sick, being admitted to hospitals, and dying, government investigators and businesses along the romaine supply chain struggled to navigate a snarl of incomplete and sometimes unavailable shipping and receiving records.

The PIRG report suggests the traceback problems can be resolved with two bullet points:

- Implement network-based food tracking technologies from farm to fork.

- Amend the federal Food Safety Modernization Act to require the collection of data during every part of the food supply chain.

Calling all recalls

A four-bullet approach is the consumer group’s solution for the Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, as well as retailers, when it comes to improving the recall process:

- Have FDA make its final guidance on naming retailers during food recalls more comprehensive by requiring disclosure for all Class I and II recalls, establishing a timeline for information release, and commitment to apply guidance to packaged goods;

Have FDA ensure enforcement of recalls by increasing consequences for companies continuing to sell products. This would include requiring information about products being pulled off shelves and requiring retailers to confirm that they executed the recall with haste;

Have FDA ensure enforcement of recalls by increasing consequences for companies continuing to sell products. This would include requiring information about products being pulled off shelves and requiring retailers to confirm that they executed the recall with haste;- Have retailers establish a more effective recall system to notify consumers that products they may have in their homes are recalled. This can involve using information from store loyalty programs to notify consumers that products they’ve purchased could be contaminated; and

- Grant USDA mandatory recall authority for contaminated food.

Moo-ve over

The intersection of animal agriculture and field-grown foods gets a fair amount of ink in the PIRG report. Concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) are known to the public as feedlots and to food safety experts as pathogen problems.

“As seen in the case of the romaine lettuce outbreak, the failure to reign in the activities of CAFOs has led to the emergence of antibiotic resistant infections that have far reaching consequences in our food supply,” according to the PIRG report. “HACCP programs may help as an ex-post review of safety standards but maintaining a clean source would go a long way in preventing contamination.”

To prevent cross-contamination from animal operations, PIRG suggests:

- Establishing and setting bacterial load for agricultural water as required by proposed rules under the Food Safety and Modernization Act (FSMA); and

- Testing water that is in the proximity of CAFOs or used for agricultural water or crop irrigation for pathogenic bacteria with molecular-based technology instead of the standard culture-based technology to shorten time needed for detection and increase accuracy.

PIRG officials said data for the recall portion of their report came from the FDA and the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service. The FSIS publishes yearly summaries on recall data on the USDA’s website. For the FDA data, the analysts submitted a Freedom of Information Act request for information on issued recalls “to help address gaps on the data on their website.”

The total number of recalls from the FSIS and FDA were combined to produce an average for the total number of recalls, according to the PIRG report. To isolate the number of FDA recalls, only recall events were counted. Duplicate recall numbers were excluded. This was done, according to the report, because there were multiple recall numbers associated with single recall events. This report was concerned with the number of recall events.

(To sign up for a free subscription to Food Safety News, click here.)