It’s time to grab a sun hat and shovel, or rake, and head to the beach to dig for clams or gather oysters. What could be a better summer outing? But time is of the essence. This season’s last chance for minus low tides, which are the best times to dig for shellfish or gather oysters, is coming up.

As reported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration the upcoming minus low tides, defined as tides that are lower than the local mean tide, will be:

West Coast, August 9-11;

East Coast south of New York, August 10-12; and

Northeast Coast, New York and states north of New York, August 10-14.

Recreational shellfish harvesters can contact their state’s wildlife or health department to find out the specific times of the low tides in their area.

About those warnings

About those warnings

As much fun it is to be out on the beach gathering fresh shellfish for meal or party, recreational shellfish harvesters need to pay attention to warnings about where it’s unsafe to harvest shellfish due to polluted water. To do otherwise could jeopardize their health, or even their lives.

Some types of infections transmitted from shellfish have a 1 in 4 death rate.

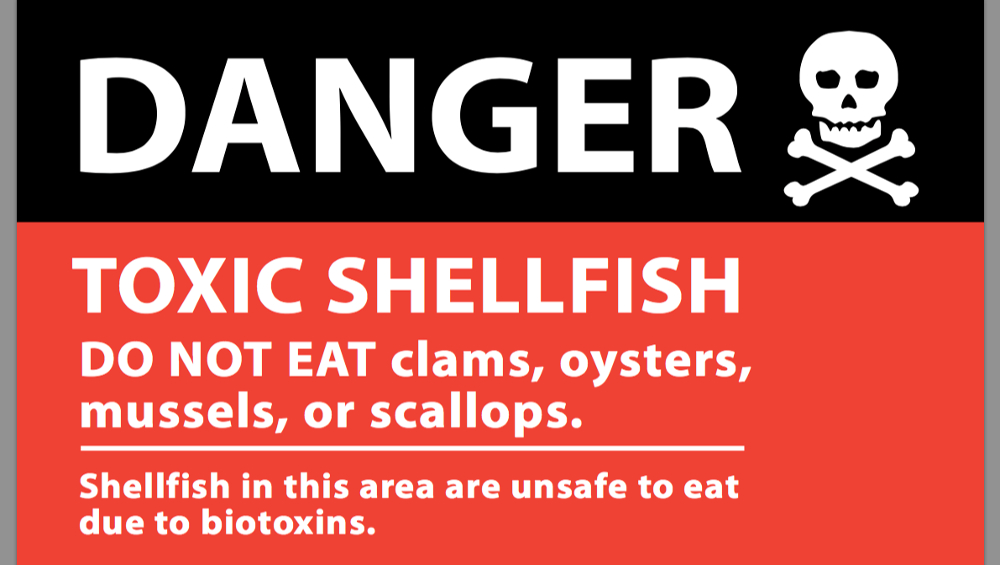

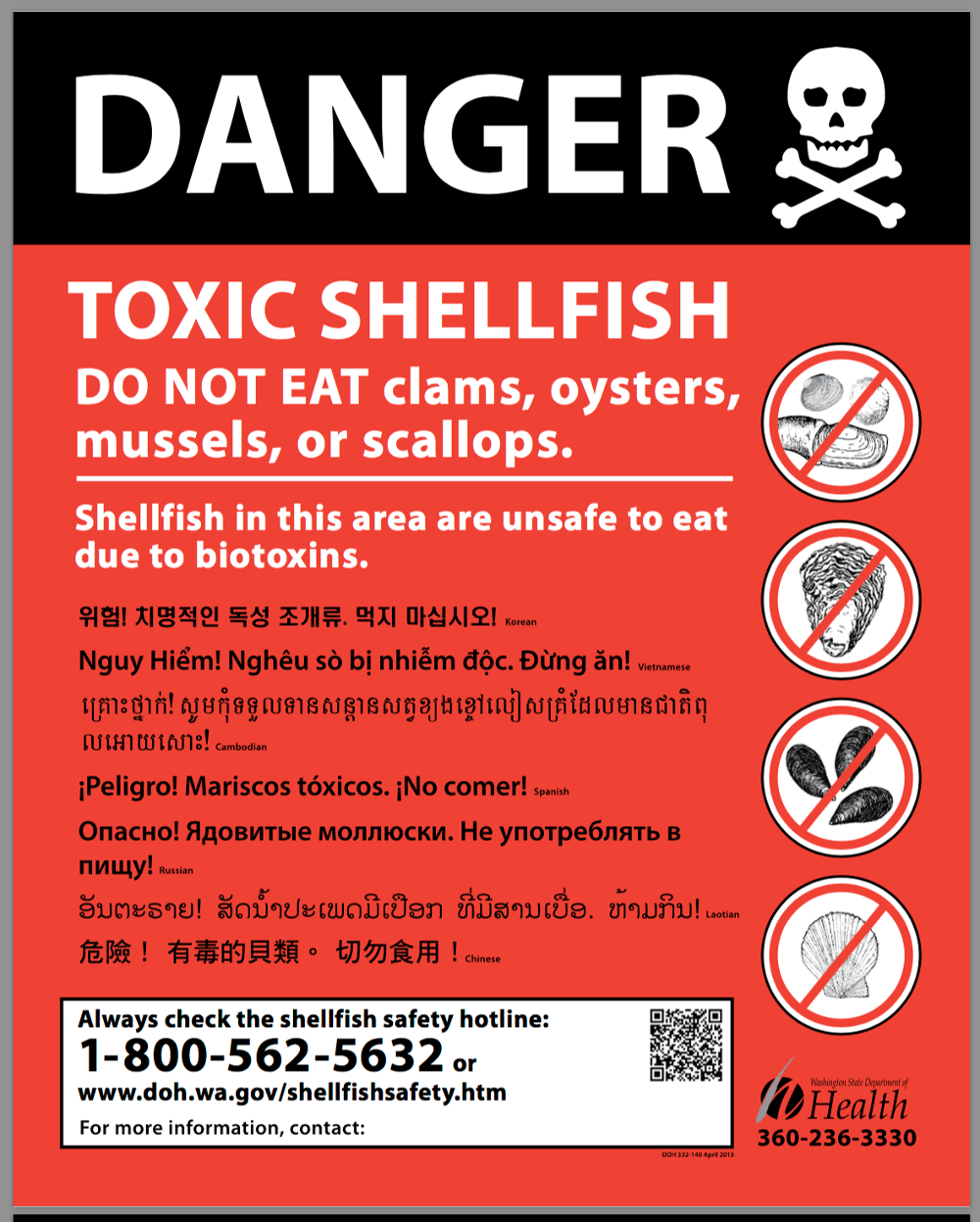

Latest news alerts about shellfish conditions are generally available through state departments of health, which also offer information to the public on shellfish hotlines, as well as by posting signs on problem beaches about precautions that need to be taken. Just looking at some of Washington state’s Department of Health signs posted on beaches when shellfish shouldn’t be harvested is enough to get the message across:

DANGER TOXIC SHELLFISH Do not eat clams, oysters, mussels or scallops. Shellfish in this area are unsafe to eat due to biotoxins.

To add emphasis to the warning, which is written in large letters in a black border, is a picture of a skull and crossbones. To make sure the message gets out to as many people as possible, the message is written in English and seven additional languages.

Another sign warns about vibrio bacteria. “Eating raw shellfish can make you sick,” it says. “Cook all shellfish to 145 degrees F (63 degrees C) for 15 seconds to kill vibrio. bacteria.” And again, the warning is posted in eight languages.

Each state has its own way of warning the public about problem beaches, which can change from month to month.

Know the difference

But wait, what’s the difference between dangerous biotoxins and vibrio bacteria? It turns out that knowing the difference can literally be a matter of life and death. While you can cook shellfish contaminated with vibrio bacteria to 145 degrees F (63 degrees C), and keep it at that temperature for 15 seconds, to kill the bacteria, that’s not the case with shellfish contaminated with biotoxins. That’s because cooking won’t kill biotoxins, nor will freezing.

“That’s a really important distinction,” said Bill Dewey, spokesman for Taylor Shellfish in Washington state. “Biotoxins don’t cook out.”

In contrast to recreational shellfish gatherers, commercial operations must follow national regulations and are monitored by the state and the Federal Drug Administration.

“We have protocols we have to follow, and we’re audited,” said Dewey.

When it comes to requirements for recreational shellfish digging or gathering, he said that knowing what he knows “I wouldn’t eat a raw oyster gathered off a beach in hot weather.”

Even so, some commercial producers such as Taylor Shellfish cater to a crowd that prefers raw oysters. The company even has three oyster bars in Seattle, one in Bellevue, and one in Vancouver, British Columbia.

“Consumer demand is really high,” he said. “They’re incredibly popular. We feel confident that we have high-quality oysters that are safe to eat.”

But again, commercial operations such as Taylor Shellfish must abide by strict regulations, especially when it comes to raw oysters.

What’s lurking in the water? Vibrio

Vibrio bacteria are natural residents of certain coastal waters. When temperatures get warmer, as they typically do between May and October, vibrio become more numerous. And that’s when they can become an even bigger human health problem.

According to the Centers for Disease Control about 80,000 people get sick with vibriosis each year in the United States. About 52,000 of these illnesses are the result of eating contaminated food, primarily raw or undercooked shellfish, particularly oysters. Other cases of vibriosis can happen when a someone with an open wound swims or wades in brackish or saltwater with dangerous levels of Vibrio.

The most commonly reported species, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, is estimated to sicken about 45,000 people in the United States each year. Symptoms Vibrio infection, which usually begin 24 hours after exposure, include watery diarrhea, abdominal cramping, nausea, vomiting, fever and chills. The illness usually lasts about three days. However, people with with chronic liver disease, diabetes, or AIDS, or compromised immune systems, should see their doctor if they have what they suspect might be vibriosis.

The CDC recently warned consumers about a current multi-state outbreak of Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections, which likely are connected to crab meat imported from Venezuela. Twelve people have so far been sickened in that outbreak and four have been hospitalized, but no deaths have been reported. The illnesses have been reported in Maryland, Louisiana, Pennsylvania, and the District of Columbia.

At this time, the CDC is advising consumers to not eat, restaurants to not serve, and retailers to not sell fresh crab meat imported from Venezuela. The product may be labeled as fresh or precooked and is commonly found in plastic containers.

The Food and Drug Administration is advising consumers to check the labels on the crab meat purchased at the retail level or verify in restaurants to ensure that it is not imported from Venezuela. The FDA also warned that the meat may look, smell, and taste normal, but is still possibly unsafe to consume.

More dangerous yet

More dangerous than Vibrio parahaemolyticus is Vibrio vulnificus, which is more common in warm coastal regions such as the Gulf of Mexico. The numbers say it all. About 1 in 4 people with this type of infection die. CDC estimates that Vibrio vulnificus causes about 205 infections in the United States every year.

Just this summer, a Florida man died after eating a raw oyster contaminated with the highly infectious Vibrio vulnificus strain of bacteria — a strain that is naturally found in salty or brackish water, especially in warmer months. According to the Florida Department of Health, there have been 16 cases and three deaths across the state from Vibrio vulnificus.

Most of the people who become infected with Vibrio vulnificus infections either eat raw or undercooked shellfish, mainly oysters, or got into water with an open wound, which allows the bacteria to enter the bloodstream.

Health officials recommend eating only thoroughly cooked oysters if recreational harvesting is done during the warm months, generally May through October. This advice also goes for oysters bought from non-commercial oyster farms, such as at a farmers market or other such outlet.

Health officials recommend eating only thoroughly cooked oysters if recreational harvesting is done during the warm months, generally May through October. This advice also goes for oysters bought from non-commercial oyster farms, such as at a farmers market or other such outlet.

This past year, a Texas woman died from Vibrio vulnificus after eating raw oysters that she and her husband bought at a market in a suburb of New Orleans. After shucking the oysters and eating them, she broke out with a rash and began to experience “respiratory distress,” which her husband at first thought was caused by an allergy. Doctors later diagnosed her with Vibriosis vulnificus. After fighting the disease for 21 days, she died on Oct. 15, 2017.

Vibrio vulnificus also made headlines this summer, when a New Jersey man contracted the infection while crabbing in a local river. The infection, which began in one of his legs, spread to his other leg and to his arms. Although doctors were treating him with antibiotics in an attempt to save his life, his condition worsened and several days ago, he was transferred to hospice, end-of-life care.

Microbiolgist Gabrielle Barbarite, a vibrio researcher trained at Florida Atlantic University, said that vibrio is not really a flesh-eating bacteria, as it has been called in various news accounts. And, no, it doesn’t degrade skin on contact.

“You have to have a pre-existing cut — or you have to eat raw, contaminated seafood or chug a whole lot of contaminated water — for it to get into your bloodstream,” Barbarite said.

Biotoxins

Marine biotoxins are poisons produced by certain types of naturally occurring microscopic algae — a type of phytoplankton. Usually, they’re in the water but in amounts too small to be harmful to people. However, when sunlight starts shining down on the water during the warmer months and the water temperature heats up, the plankton can rapidly reproduce and you’ll get “blooms,” often referred to as red tides, even though they’re not always red and not caused by tides. These type of blooms are often harmless to humans.

But it’s a different matter in the case of harmful algal blooms, often referred to as HABs. And that’s where humans who eat shellfish come into the picture. Shellfish with hinged shells — oysters, clams and mussels, for example — eat algae, and HABs create a lot of algae for them to dine on. The problem is that when shellfish eat toxin-producing algae, the toxins can concentrate in their tissue. And while biotoxins don’t harm shellfish, they can accumulate to levels that can poison people who eat them — or even kill them.

According to CDC, there are several different types of shellfish biotoxin poisonings primarily associated with shellfish. One of them, paralytic shellfish poisoning, often referred to as PSP, can be fatal, especially in children. Symptoms, which can appear in a matter of minutes after eating the contaminated shellfish, can include digestive problems and also numbness or burning around the mouth, gums, tongue and then progressing to the neck, arms, legs and toes.

Another biotoxin illness is amnesic shellfish poisoning, caused by eating shellfish with the toxin domoic acid. Neurologic signs are severe and can take up to three days to develop. These include dizziness, disorientation, visual disturbances, short-term memory loss, motor weakness, seizures, increased respiratory secretions and life-threatening irregular heartbeats. However death is rare.

Two others are neurotoxic shellfish poisoning, which is generally not life-threatening, although hospitalization is recommended until all other causes have been ruled out. When the toxin is aerosolized in rough surf, as has been the case this year in Florida’s huge “red tide,” exposed people can develop a syndrome that includes pink eye, runny nose, and a nonproductive cough.

Diarrheal shellfish poisoning can damage the intestinal mucous membrane, making it very permeable to water. This causes significant diarrhea as well as nausea, vomiting and abdominal cramps. Usually not life-threatening, the symptoms can strike within a few minutes to an hour after eating contaminated shellfish and can last for about a day. Serious dehydration can occur.

Let’s start digging, or gathering

But first, some food-safety basics about oysters.

Instead of digging for them, you actually walk along the beach gathering them. At low tide, of course, otherwise they’re under water. It’s best to gather them as soon as possible after the tide goes out. That way, they’re fresher. Don’t harvest them if they’ve been exposed to direct sunlight for more than two hours.

“When they’re out of the water and in the sun, they become little incubators,” Taylor Shellfish’s Dewey said. “The odds are pretty high that the bacteria will start multiplying to dangerous levels.”

It goes without saying, of course, that recreational oyster gatherers should pay attention to any signs posted on the beach. If there’s a warning about biotoxins, they shouldn’t even think about harvesting them, regardless if they had plans to cook them or eat them raw.

“Biotoxins don’t cook out,” Dewey said,

Some states require recreational harvesters to shuck the oysters and leave the shells on the beach so that the spat attached to the shells can reproduce. In that case, the shucked oysters should immediately be put in a container on ice, and they must be kept cold until eaten. That’s also true for oysters in the shell. Even oysters that will be cooked should be kept cold until cooked.

As in the case of all shellfish, oysters should be thoroughly cooked. Just because they open up, doesn’t mean they’re thoroughly cooked. They actually need to reach an internal temperature of 145 degrees F and stay at that temperature for 15 seconds. This is especially important when barbecuing oysters on a grill because many people think they’re ready to eat once they open up.

Tips from Washington state’s Department of Health are relevant in all states.

Storing shellfish

When still in their shell, all fresh shellfish should be stored in an open container in the refrigerator. Don’t put them in a closed container. Instead, place a damp towel on top to maintain humidity. Never store shellfish in water. They will die and may spoil. Any shellfish that are open and don’t close when tapped are dead. Throw them out.

Storage times for shellfish vary.

Shellfish that close their shells completely can be stored for up to 7 days. This includes oysters, littlenecks, butter clams, and cockles. Exception: Mussels can be stored for only 3 to 4 days.

The types of shellfish that cannot completely close their shells — horse clams, softshell clams, geoducks, and razor clams, for example — can be stored for 3 to 4 days.

Shucked shellfish (shellfish that have been removed from their shells) should keep in a refrigerator for up to three days. In a freezer, they should keep for up to three months.

Cooked shellfish should keep in the refrigerator for up to two days and in a freezer up to three months.

Shellfish taken from the freezer and thawed in a refrigerator should stay in good condition for up to two days. But once thawed, do not refreeze. Only defrost them in the refrigerator, never on a kitchen counter or other surface outside of the refrigerator.

Cooking shellfish

To ensure proper food safety, shellfish must be cooked to an internal temperature of at least 145 degrees F. Since it is often impractical to use a food thermometer to check the temperature of cooked shellfish, here are some tips and recommended ways to cook shellfish safely:

The FDA suggests boiling shucked oysters for 3 minutes, frying them in oil at 375 degrees F for 10 minutes, or baking them at 450 degrees F for 10 minutes.

The FDA suggests steaming oysters in the shell for 4 to 9 minutes or boiling them for 3 to 5 minutes after they open.

Scallops, depending on size, take 3 to 4 minutes to cook thoroughly.

(To sign up for a free subscription to Food Safety News, click here.)