There was a lot of hand-washing going on during the Northwest Washington Fair last week in Lynden, WA. Yes, there were the usual farm exhibits, carnival rides, food booths, music, talent shows, and much more. But the 24 hand-washing stations placed around the animal barns, along with a team of specially trained “Hand-Washing Ambassadors,” underscored the fair’s commitment to providing a safe and healthy gathering place for the approximately 200,000 people who attend the popular event each year.

- Avoid hand-to-mouth activities, such as eating, applying lip balm, and biting fingernails while in the animal exhibit areas.

- Avoid touching animals and other potentially contaminated surfaces in animal exhibit areas when possible.

- Always wash hands immediately upon leaving animal exhibit areas.

- Always wash hands again immediately before eating.

- Avoid taking strollers into barns where the wheels may spread contamination back to cars and home settings.

- Routinely clean and disinfect surfaces that people’s hands may contact as this is an important element of reducing pathogen loads in animal-exhibit areas.

Thumbs up for hand-washing

The health department’s exhibit also had a poster including common myths about hand-washing. For example: You don’t have to dry your hands after washing them (wrong). It doesn’t matter how long you wash your hands as long as you use soap (wrong). Using gloves makes hand-washing unnecessary (wrong). And, hand sanitizers can replace washing your hands with soap and water (wrong because they don’t remove “bad bacteria” as well as soap.) There’s a quick rundown here on hand-washing from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Baron said the hand-washing stations had proven to be very popular, with 350 passport cards turned in the first day. “It exceeded our expectations,” he said. Kunesh agreed. “We’re definitely seeing a lot more people stopping and washing their hands,” he said. “That’s good. It means they’re learning how important it is.” But is it enough? Although proper hand-washing after being around animals and before eating is an excellent way to help prevent E. coli, there can be more to it than that. That’s because E. coli can actually be airborne. That was likely the case in 2002 at the Lane County Fair in Eugene, OR, when 82 fairgoers (74 confirmed cases and 8 presumed cases), almost two-thirds of them children younger than six, came down with E. coli infections. It was baffling to say the least, but some sleuthing on the part of Dr. William Keene, then a senior epidemiologist with Oregon Public Health Division, revealed that all three samples that tested positive in the goat and sheep expo hall were in locations 15 to 18 feet up off the ground. He told a reporter with a Eugene newspaper that finding it there “indicates it blew up there.” The assumption was that once the bacteria were airborne, they could also settle down on railings, animal fur, human skin or food people had in the barn. Perhaps some of the people in the barn had even swallowed the contaminated dust. That meant, Keene said, that fairgoers wouldn’t have even had to touch an animal to get infected. Although hand-washing is considered the single most effective way to prevent the spread of E. coli, it didn’t appear to be the silver bullet during the Lane County Fair. The percentage of sickened people who washed their hands after leaving the animal barns — 31 percent — was only slightly lower than the 36 percent of healthy people who washed their hands.

The health department’s exhibit also had a poster including common myths about hand-washing. For example: You don’t have to dry your hands after washing them (wrong). It doesn’t matter how long you wash your hands as long as you use soap (wrong). Using gloves makes hand-washing unnecessary (wrong). And, hand sanitizers can replace washing your hands with soap and water (wrong because they don’t remove “bad bacteria” as well as soap.) There’s a quick rundown here on hand-washing from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Baron said the hand-washing stations had proven to be very popular, with 350 passport cards turned in the first day. “It exceeded our expectations,” he said. Kunesh agreed. “We’re definitely seeing a lot more people stopping and washing their hands,” he said. “That’s good. It means they’re learning how important it is.” But is it enough? Although proper hand-washing after being around animals and before eating is an excellent way to help prevent E. coli, there can be more to it than that. That’s because E. coli can actually be airborne. That was likely the case in 2002 at the Lane County Fair in Eugene, OR, when 82 fairgoers (74 confirmed cases and 8 presumed cases), almost two-thirds of them children younger than six, came down with E. coli infections. It was baffling to say the least, but some sleuthing on the part of Dr. William Keene, then a senior epidemiologist with Oregon Public Health Division, revealed that all three samples that tested positive in the goat and sheep expo hall were in locations 15 to 18 feet up off the ground. He told a reporter with a Eugene newspaper that finding it there “indicates it blew up there.” The assumption was that once the bacteria were airborne, they could also settle down on railings, animal fur, human skin or food people had in the barn. Perhaps some of the people in the barn had even swallowed the contaminated dust. That meant, Keene said, that fairgoers wouldn’t have even had to touch an animal to get infected. Although hand-washing is considered the single most effective way to prevent the spread of E. coli, it didn’t appear to be the silver bullet during the Lane County Fair. The percentage of sickened people who washed their hands after leaving the animal barns — 31 percent — was only slightly lower than the 36 percent of healthy people who washed their hands.

Buller said that Dr. Steven Neel, who developed the program, came to the fair, looked it over and gave some recommendations. Since then, he’s been back twice. “It’s a very good program — a great resource,” he said, adding that it includes reports, checklists and protocols. Following the program’s recommendations, the fair added some additional hand-washing stations and restricted food and drinks in the barns. Pressure washing and disinfecting the barns was another step in the process of keeping the barns as safe as possible for fairgoers. Dust control is also important, and teams regularly wiped down the pen railings with bleach or a disinfecting chemical during the fair. How confident does Buller feel about the safety of the fair? “Very confident,” he said. “But there will always be some inherent risk. There will never be zero risk.” As for the hand-washing station in front of every barn exit, Buller said that in the first year or two, some people used them. But with the public becoming more aware of the importance of preventing E. coli, their use has significantly increased. “Now if you watch the barns, almost everyone out the door makes sure their kids use them,” he said. Buller is optimistic that steps like this will help keep county fairs going. “Agriculture is enjoying a new regrowth of interest, and people are becoming more aware,” he said. Inherent risk with fairs and petting zoos?

Buller said that Dr. Steven Neel, who developed the program, came to the fair, looked it over and gave some recommendations. Since then, he’s been back twice. “It’s a very good program — a great resource,” he said, adding that it includes reports, checklists and protocols. Following the program’s recommendations, the fair added some additional hand-washing stations and restricted food and drinks in the barns. Pressure washing and disinfecting the barns was another step in the process of keeping the barns as safe as possible for fairgoers. Dust control is also important, and teams regularly wiped down the pen railings with bleach or a disinfecting chemical during the fair. How confident does Buller feel about the safety of the fair? “Very confident,” he said. “But there will always be some inherent risk. There will never be zero risk.” As for the hand-washing station in front of every barn exit, Buller said that in the first year or two, some people used them. But with the public becoming more aware of the importance of preventing E. coli, their use has significantly increased. “Now if you watch the barns, almost everyone out the door makes sure their kids use them,” he said. Buller is optimistic that steps like this will help keep county fairs going. “Agriculture is enjoying a new regrowth of interest, and people are becoming more aware,” he said. Inherent risk with fairs and petting zoos?

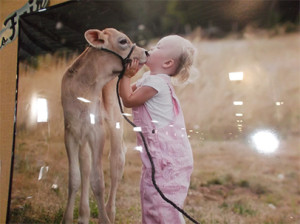

- Animals are more likely to shed pathogens such as E. coli O157:H7 because of the stress they suffer from prolonged transportation, confinement, crowding, and increased handling.

- Co-mingling increases the probability that animals shedding pathogens will infect other animals.

- The presence of certain enteric pathogens such as E. coli O157:H7 is higher in young animals, which are frequently in petting zoos and educational programs, more so than in mature animals.

- Shedding of these types of pathogens and Salmonella organisms is highest in the summer and fall, when substantial numbers of traveling exhibits, agricultural fairs, and petting zoos are scheduled.

The report also points out that although farm residents might have some acquired immunity to certain pathogens, livestock exhibitors have become infected with E. coli O157:H7 in outbreaks at fairs. Why E. coli O157:H7 is so dangerous First discovered in 1982, E. coli O157:H7 is an especially virulent form of the bacterium E. coli. A mere 50 of them can make someone ill. They’re also difficult to detect; 100,000 can fit on the head of a pin. Yet E. coli O157:H7 does not sicken cows and other livestock that have it in their systems. (Making things more complicated, it can come and go, meaning that a cow that has it won’t always have it, and a cow that doesn’t have it can get it.) But because the animals that do have E. coli in their systems shed it through their manure, people can become exposed to it through various ways, such as petting animals that have traces of manure on their hides, or coming into contact with contaminated bedding, rails, fencing or gates. These people can then become ill if they don’t properly wash their hands before eating. In other words, you don’t want even a microscopic trace of poop on your hands when you eat. And you don’t want any of the airborne bacteria to get on your food, hands, or silverware.  In addition, a person with traces of E. coli on his or her hands, clothing, or mouth can actually infect another person. After the Milk Makers Fest, nine people (including a baby) who didn’t attend the event came down with E. coli through what is referred to as secondary infections. For the most part, it’s young children and babies, the elderly, and those whose systems are immunocompromised who are the most vulnerable. And they’re also the ones who become the sickest from it. Symptoms range from slight digestive discomfort to bloody diarrhea and extreme pain. An occasional complication of E. coli is hemolytic uremic syndrome, or HUS, a serious kidney condition that can be fatal. Symptoms usually occur 3-4 days after exposure, but they may be as short as 1 day or as long as 10 days. Anyone with these symptoms should contact a doctor. E. coli can also be foodborne, for example, in hamburger that hasn’t been cooked long enough to kill bacteria that might have gotten on the meat during slaughtering, or in raw milk, which hasn’t been pasteurized. It can also contaminate water. Go here for more information about E. coli O157:H7.

In addition, a person with traces of E. coli on his or her hands, clothing, or mouth can actually infect another person. After the Milk Makers Fest, nine people (including a baby) who didn’t attend the event came down with E. coli through what is referred to as secondary infections. For the most part, it’s young children and babies, the elderly, and those whose systems are immunocompromised who are the most vulnerable. And they’re also the ones who become the sickest from it. Symptoms range from slight digestive discomfort to bloody diarrhea and extreme pain. An occasional complication of E. coli is hemolytic uremic syndrome, or HUS, a serious kidney condition that can be fatal. Symptoms usually occur 3-4 days after exposure, but they may be as short as 1 day or as long as 10 days. Anyone with these symptoms should contact a doctor. E. coli can also be foodborne, for example, in hamburger that hasn’t been cooked long enough to kill bacteria that might have gotten on the meat during slaughtering, or in raw milk, which hasn’t been pasteurized. It can also contaminate water. Go here for more information about E. coli O157:H7.

(To sign up for a free subscription to Food Safety News, click here.)