Opinion

I will spare you the list of hepatitis A cases that I have been involved with since 1998 when I represented 30 people exposed in a Seattle, Washington Subway restaurant, including one child who suffered acute liver failure requiring an emergency liver transplant.

There have been dozens in the last 23 years, many with tragic consequences. Yet, here we are once again.

Now, according to Roanoke Virginia health officials, as of today at least three people are dead in connection with an outbreak of hepatitis A that has been linked to the Famous Anthony’s restaurant chain. Health officials have also confirmed at least 49 cases of the illness, with at least 31 people requiring hospitalization for acute liver failure. There will likely be additional, secondary cases, in those who cared for close family members.

Health officials have confirmed that one person with hepatitis A worked at three separate Roanoke locations of the Famous Anthony’s chain and exposed patrons to this human fecal virus.

Hepatitis A is considered preventable via good personal hygiene practices such as thorough handwashing and glove wearing. Hepatitis A is the only vaccine preventable foodborne illness. Hepatitis A vaccines are available, and nationwide are given out free by local health departments, or at a cost of less than $100.

The first known fatality in the Famous Anthony’s outbreak was identified as Roanoke County resident James Hamlin, 75, who died October 8th from hepatitis A complications after eating at one of the Famous Anthony’s. I represent James’s widow and the Hamlin family. Two more deaths were confirmed Friday. One of the families will be speaking publicly in the following days.

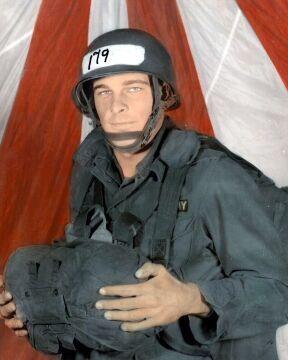

James Hamlin’s family told local news that the U.S. Army veteran, who served as a Green Beret during the Vietnam War era, seemed strong and healthy until suddenly feeling nauseous and fatigued one day in August. After his symptoms persisted, he was admitted to a hospital and died 10 days later of acute liver failure.

He survived Vietnam but dies due to exposure to an unvaccinated food handler who did not properly was his or her hands or wear gloves.

Here is what the CDC continues to say about vaccinating food handlers:

Why does CDC not recommend all food handlers be vaccinated if an infected food handler can spread disease during outbreaks?

CDC does not recommend vaccinating all food handlers because doing so would not prevent or stop the ongoing outbreaks primarily affecting individuals who report using or injecting drugs and people experiencing homelessness. Food handlers are not at increased risk for hepatitis A because of their occupation. During ongoing outbreaks, transmission from food handlers to restaurant patrons has been extremely rare because standard sanitation practices of food handlers help prevent the spread of the virus. Individuals who live in a household with an infected person or who participate in risk behaviors previously described are at greater risk for hepatitis A infection.

CDC, you miss the point, granted food service workers are not more at risk of getting hepatitis A because of their occupation, but they are a risk for spreading it to customers. Also, food service are low paid jobs that certainly have the likelihood of being filled by people who are immigrants, where hepatitis A might be endemic, or people who have been recently homeless.

What should I do if I have eaten at a restaurant that has reportedly had a hepatitis A-infected food handler?

If you have any questions about potential exposure to hepatitis A, call your health professional or your local or state health department who can help you to learn if you were recently exposed to hepatitis A virus at that restaurant, have not been vaccinated against hepatitis A, and might benefit from either hepatitis A vaccine or an injection of immune globulin. However, the vaccine or immune globulin are only effective if given within the first 2 weeks after exposure. A health professional can decide what is best based on your age and overall health.

The problem here is that the Famous Anthony’s employee worked while infectious during the last half of August. There was no announcement that there had been a risk of exposure until the end of September – two weeks too late for vaccine or immune globulin to be effective.

I will also spare you the numerous times I pleaded with the CDC, local and state health officials, and restaurants to require hepatitis A vaccinations for food handlers. Let’s be clear, had the food handler who exposed patrons of three Famous Anthony’s restaurants been vaccinated against hepatitis A, we would not be having this discussion, and I would not be representing over two dozen people hospitalized and two that lost loved ones. I would also not be suing Famous Anthony’s which will likely cost millions of dollars and/or drive them into bankruptcy.

My guess is that the cost of a hepatitis A vaccine looks very appetizing at this point?

(To sign up for a free subscription to Food Safety News, click here.)