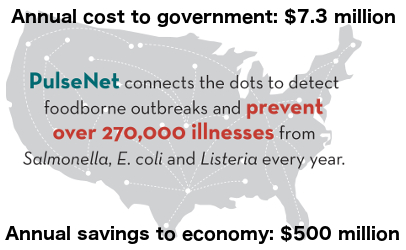

Those who believe government should operate like a successful business ought to be happy about the ROI on the $7.3 million annual cost of PulseNet, which is saving half a billion each year by preventing an estimated 270,000 illnesses. By using DNA analysis of pathogens and sharing data, the network of 83 state and federal labs that make up PulseNet connects individuals across the country who have foodborne illnesses from the same source. Marking the 20th anniversary of PulseNet this year, officials with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have said they have known for some time — anecdotally — that the network and database have been making a difference. Research on the impact of PulseNet published Wednesday in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine replaced anecdotal evidence with hard science. Financial support for the research came from the CDC, through the Association of Public Health Laboratories. Researchers led by Robert L. Scharff of Ohio State University and Craig Hedberg of the University of Minnesota assembled data collected between 1994 and 2009 and analyzed it between 2010 and 2015. They reported PulseNet identifies about 1,750 disease clusters each year with about 250 of them involving multiple states. “Conservatively, accounting for underreporting and under-diagnosis, 266,522 illnesses from Salmonella, 9,489 illnesses from Escherichia coli (E. coli), and 56 illnesses due to Listeria monocytogenes are avoided annually. This reduces medical and productivity costs by $507 million,” according to the research abstract. “Additionally, direct effects from improved recalls reduce illnesses from E. coli by 2,819 and Salmonella by 16,994, leading to $37 million in costs averted.”

Those who believe government should operate like a successful business ought to be happy about the ROI on the $7.3 million annual cost of PulseNet, which is saving half a billion each year by preventing an estimated 270,000 illnesses. By using DNA analysis of pathogens and sharing data, the network of 83 state and federal labs that make up PulseNet connects individuals across the country who have foodborne illnesses from the same source. Marking the 20th anniversary of PulseNet this year, officials with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have said they have known for some time — anecdotally — that the network and database have been making a difference. Research on the impact of PulseNet published Wednesday in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine replaced anecdotal evidence with hard science. Financial support for the research came from the CDC, through the Association of Public Health Laboratories. Researchers led by Robert L. Scharff of Ohio State University and Craig Hedberg of the University of Minnesota assembled data collected between 1994 and 2009 and analyzed it between 2010 and 2015. They reported PulseNet identifies about 1,750 disease clusters each year with about 250 of them involving multiple states. “Conservatively, accounting for underreporting and under-diagnosis, 266,522 illnesses from Salmonella, 9,489 illnesses from Escherichia coli (E. coli), and 56 illnesses due to Listeria monocytogenes are avoided annually. This reduces medical and productivity costs by $507 million,” according to the research abstract. “Additionally, direct effects from improved recalls reduce illnesses from E. coli by 2,819 and Salmonella by 16,994, leading to $37 million in costs averted.”  The power of information In addition to helping preventing outbreaks from spreading unchecked, CDC officials say PulseNet has had an impact on the food industry. Many products and food handling practices are safer today because of investigations that PulseNet initiated, CDC officials said in a news release announcing the publication of the research. Changes include alterations to production procedures and facilities, new or improved guidance and better-informed policies and regulations. “PulseNet is an integral part of our food-safety system and it helps improve the quality and safety of all the food that we eat,” said John Besser, deputy chief of the CDC’s enteric diseases laboratory branch, in an interview published by Ohio State University. “Part of that effect is containing outbreaks, but a really significant portion of the benefit is giving feedback to the food industry and the regulatory agencies so they can make food safer.” The lead researcher from Ohio State University agrees with that assessment. Scharff said analysis of the data suggests PulseNet has contributed to a food safety climate shift toward better practices, quicker action when problems are identified and better self-policing by business and industry to avoid lawsuits and lost revenue. “The PulseNet system makes possible the identification of food safety risks by detecting widespread or non-focal outbreaks. This gives stakeholders information for informed decision making and provides a powerful incentive for industry,” according to the research abstract. “Furthermore, PulseNet enhances the focus of regulatory agencies and limits the impact of outbreaks. The health and economic benefits from PulseNet and the foodborne disease surveillance system are substantial.”

The power of information In addition to helping preventing outbreaks from spreading unchecked, CDC officials say PulseNet has had an impact on the food industry. Many products and food handling practices are safer today because of investigations that PulseNet initiated, CDC officials said in a news release announcing the publication of the research. Changes include alterations to production procedures and facilities, new or improved guidance and better-informed policies and regulations. “PulseNet is an integral part of our food-safety system and it helps improve the quality and safety of all the food that we eat,” said John Besser, deputy chief of the CDC’s enteric diseases laboratory branch, in an interview published by Ohio State University. “Part of that effect is containing outbreaks, but a really significant portion of the benefit is giving feedback to the food industry and the regulatory agencies so they can make food safer.” The lead researcher from Ohio State University agrees with that assessment. Scharff said analysis of the data suggests PulseNet has contributed to a food safety climate shift toward better practices, quicker action when problems are identified and better self-policing by business and industry to avoid lawsuits and lost revenue. “The PulseNet system makes possible the identification of food safety risks by detecting widespread or non-focal outbreaks. This gives stakeholders information for informed decision making and provides a powerful incentive for industry,” according to the research abstract. “Furthermore, PulseNet enhances the focus of regulatory agencies and limits the impact of outbreaks. The health and economic benefits from PulseNet and the foodborne disease surveillance system are substantial.”

Sponsored by Marler Clark