She’s 18 now and hasn’t visited her aunt for several years. But like her aunt, she has a strong interest in cooking. Going into the kitchen, she’s pleased to see that her aunt has kept up with the times. Years ago, she was one of the first in the family to get a microwave and she recently got an air fryer.

“But, what’s that?” the young girls asks as she points to something she has never seen before.

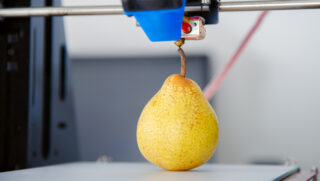

“Oh, that,” says her aunt smiling, “is a 3D printer.”

“Here in the kitchen?”, the young girl asks. “What’s it doing here?

“I can make all kinds of food — including steaks with it,” her aunt says, obviously enjoying her niece’s bewilderment.

No, this isn’t a true-to-life scenario — not yet anyway. But it does lend a hint of what lies ahead in the almost hard-to-believe changes coming to the world of food — in this case 3D food printers.

And while some advocates say that 3D printed food is a highly anticipated innovation, others are not so sure. Just listen to what some of the shoppers, young and old, at a farmers market in Washington state had to say about it.

“Weird. How do they even do that?”

“Bizarre.”

“Too futuristic for me.”

“We’re old-fashioned,” said a Washington State University Master Gardener, who was at the market to provide answers to gardeners’ questions. “We think of food as coming from growing things.”

“Is it nutritious?” asked one of her fellow Master Gardeners. “That’s the whole purpose of food.”

“Scary. No thank you.”

“No way I’d get one for our household. We were slow to even get a microwave.”

“Maybe for decorating cakes, but definitely not for real food.”

On the other side of the coin, market manager Jeremy Kindlund said he thought it sounded exciting. “I can see a lot of potential in it,” he said.

He’s not alone in that outlook. In fact, a recent survey done by Hub.com, 3D printing experts, revealed that 3D printed food garnered an impressive number of Google searches per month when looking at a range of 3D printed advancements.

Coming in second in the poll with 9,800 Google searches per month, 3D printed food followed 3D printed houses, which garnered 76,000 searches. Included in the 3D printed items in the survey were cars, shoes, human organs, drones, rockets, furniture, robots, dentures and even printed dresses.

In the category of 3D printed food, meat received 4,500 searches a month, thanks to what Hubs.com refers to as a “breakthrough” advancement last year.

That’s when an Israeli bioprinting company announced that it had actually printed a 104-gram (3.67 ounces) cultivated steak, perhaps the largest cultured steak produced until that time.

Simply put, cultured meat is not the same as plant-based meat. Instead it is produced from beef cells by taking a biopsy from a living cow and growing it in a nutritious medium until there’s enough critical mass to make the cells into bio-ink. The bio-ink is then printed using the company’s bio-printer. From there the printed steak is left in an incubator to allow the stem cells to differentiate into the fat and muscle cells that form the tissues found in steak. And, yes, it’s real meat.

This doesn’t involve slaughtering a cow to get beef — a decided plus for people who don’t like the thought of killing animals.

It’s also a plus for concerns about climate change because it means herds of cattle don’t have to be raised, and then slaughtered, to get beef, which adds up to impressive savings in water and other environmental benefits.

Once again, climate change comes into the picture. And beyond that scientists in favor of 3D printing point to the vast amount of resources needed to raise livestock, which is why they see this technology as a solution to meeting the pressing needs of the world’s growing population.

Regardless of their origin, plant or animal, it increasingly seems like the meat of the future will be coming not from animals, but from 3D printers, says an article in IDTechEx.

Then there’s the more down-to-earth prediction: Before long, every consumer’s kitchen will have a 3D food printer on one of its counter tops — just another kitchen tool to make preparing meals (or snacks) easier and faster.

How do food printers work?

Most people know what a printer is. It prints out copies of pages you’ve put information on. That technology has been around for a long time. But a printer to make food? And what’s this about climate change? And protecting the environment?

Actually, there’s nothing all that complicated about how a 3D food printer works, at least the concept of how one works. Do you remember the pizza vending machines that popped up in 2015? In that case, dough is prepared and extruded from one of the printer’s cartridges onto a plate. Next, the dough is topped with tomato sauce and cheese and then sent to the oven — all of this in the same machine. Think of this as a primitive 3D food printing process.

Since then, advances have been made that involve using laser technology to heat up the food — again all in the same machine. Just imagine, pushing a button on the printer for ravioli and having cooked ravioli ready to eat when you open the printer’s door.

All of this, or at least some of it, is still in the future, but the future has a way of coming faster than we imagine.

Getting down to basics, most 3D food printing is done by feeding food materials such as doughs, cheeses, frostings and even raw meats into syringe-like containers that are then extruded from them as the nozzle is moved around “trace shapes” on a “plate” and forms layers one at a time. That’s how you get layers, such as for pizza.

Will you find this technology in a fast-food restaurant? Hardly. Instead, these printers are found in gourmet restaurants and fancy bakeries. Or you can go to special events featuring 3D food printers.

And there’s even a traveling restaurant that features not only 3D printed food but also tables, chairs, silverware and more made from 3D printing.

But what about nutrition?

In Lynette Kucsma’s TedxHigh Point talk she lets her audience know right away that she has always considered herself a healthy eater. Which is why at first she was so skeptical about foods made using 3D printing.

But as she did some research on this, she discovered that she could eat healthy when using a 3D printer. In fact, she is now the co-founder and chief marketing officer at Natural Machines, the makers of Foodini.

When describing the status of this new technology, she told her audience: “This is science fact, not science fiction.”

She goes so far as to predict that 3D printers will follow the path of microwaves. When they were first introduced in the 1970s, “people didn’t get it,” she said. Some people even thought they could cause cancer. They’d ask “why do I need one when I already have a perfectly good oven in my kitchen?”

But things have changed, she said. Microwaves are now in 90 percent of our kitchens.

She predicted that 3D printers will follow the same route, but at a much faster rate simply because these days, technological advances move so fast. Before long, she said, they’ll be the size of a microwave and be a common kitchen appliance.

Turning to nutrition, she told her audience “Let’s print more of our food using fresh, healthy, real, wholesome ingredients. Let’s get away from packaged processed foods.”

She pointed out that by getting away from these foods, you’ll be eating more nutritious foods instead.

“And that’s healthier,” she said.

What about cost?

Filemon Schoffer, cofounder and CCO of Hubs.com, a 3D printing expert, said that the prices of 3D food printers vary depending on their features and audience.

A precise printer that can reach high nozzle temperatures is likely to be much more expensive, he said, and more appealing to businesses.

However, for those looking to get started at home you can get a basic model for around $100 to $500. Advanced home users are likely to spend around $300 to $1,000, while commercial users who want a more sophisticated model, can expect to pay over $5,000.

He said there are many models available to purchase for home use, however it’s important to do your research before spending money on a 3D printer, as there are so many different options.

What about food safety?

No problems with food safety, say the printers’ advocates, but that’s only if the food has been prepared in a machine that’s sterile and if the preparer follows sanitary procedures. No different from what’s necessary in any kitchen.

However, in The Essential Guide to Food Safe 3D Printing: Regulations, Technologies, Materials, and More, food safety with 3D printing is not a simple matter that will boil down to a clear yes or no answer. Producing 3D printed parts for food contact items requires careful consideration of the risks depending on their intended use.

A 3D printed part can turn into a petri dish squirming with bacteria within weeks. Even though some materials will survive the dishwasher, so will dangerous bacteria such as E. coli and Salmonella that live in the little nooks and crannies. Some toxic molds find favorable growth conditions on several types of plastic and are hard to remove. Neither cleaning with bleach nor microwaving is an option for eliminating germs.

No matter what, food that is consumed by people must meet strict safety standards.

Future

As 3D printing technology continues to soar, new research predicts the overall 3D printing market will continue to grow by 24 percent to reach $44.5 billion by 2026, according to research done by Hubs.com.

As it is now, there are dozens of food printers available on the market, thanks in part to public interest and the rapid growth in the technology involved.

Filemon Schoffer, cofounder and CCO of Hubs.com, said that overall, more signs of growth in 3D printing will be seen in 2022 and beyond, thanks to enhanced automation, scalable quality controls, reduced processing costs, and further industry consolidation.

He said, key factors such as this “will help 3D printing become the robust industrial manufacturing process that befits its massive potential.”

(To sign up for a free subscription to Food Safety News, click here)