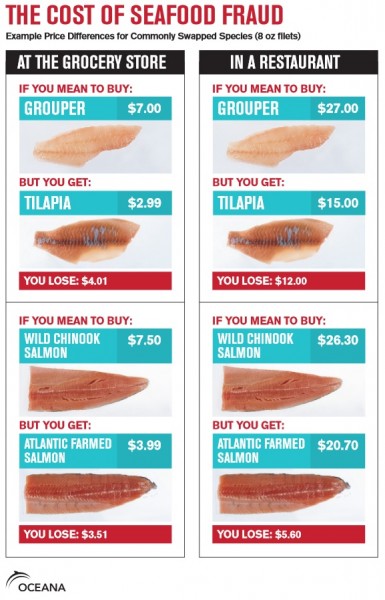

In a follow-up to its February report finding one-third of the seafood tested in the United States is mislabeled according to U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines, an oceans-protection group says Americans are paying a high price for fish fraud. Oceana, an international group advocating for protection of the world’s oceans, says that swapped species can cost consumers twice as much when cheaper counterparts are sold as premium choices. Just as horsemeat was sold as beef all over Europe when its price was only about one-fifth that of the more-expensive meat, the new report from Oceana says that seafood fraud is practiced on consumers when less-expensive and less-desirable species are passed off as high-quality fish. “Swapping a lower-cost fish for a higher-value one is like ordering a filet mignon and getting a hamburger instead,” says report author Margot Stiles. “If a consumer eats mislabeled fish even just once a week, they could be losing up to hundreds of dollars each year due to seafood fraud.” According to the Oceana study, substitution of a lower-cost species such as tilapia for more-expensive grouper could cost consumers an extra $10 for an eight-ounce filet in a restaurant, and the common substitution of Atlantic farmed salmon for wild Chinook salmon adds another $5 to a restaurant bill. Fish fraud also occurs in grocery stores when cheaper substitutes are used in place of higher-cost fish to rip off about $4 each from consumers, the study says. Oceana turned to seafood experts and about 300 menus in 12 different cities to come up with its estimates for how much fish substitutions cost consumers. “Consumers deserve to know their seafood is safe, legally caught, and honestly labeled, including information like where, when and how it was taken out of the ocean, “ Stiles said. “The more information that follows the fish, the harder it will be for fraudsters to rip off American consumers.” The 23-page Oceana report on fish fraud says part of the problem is that seafood follows a complex path “from boat to plate.” Fish often cross ocean basins and multiple countries before reaching the final point of sale. Oceana says that each stop in the supply chain is an opportunity for fraud. “Without traceability, or requiring information to follow the fish through the supply chain that is transparent and verifiable, consumers can be subject to fraud at every step the way,” the group says. Oceana supports the Safety and Fraud Enforcement for Seafood (SAFE) Act that has been pending in Congress since March. The group says it has more than 500,000 members worldwide. The fish fraud report also notes that Americans have doubled their seafood consumption in the past 50 years and that some of today’s most popular fish were not even sold in the U.S. until recent years. Freshwater Tilapia, for example, has gone from virtually unknown to the fifth most popular U.S. seafood, mostly in the past decade. Another indicator is the number of sushi bars in the U.S., which have grown five-fold in the past 10 years. More than 5,000 grocery stores also sell sushi today. In total, Americans are eating about $80 billion worth of fish annually. Oceana says 1,700 species of fish and shellfish are sold in the U.S. and that most consumers have a difficult time comparing price, quality, origin and other factors. The study found seafood labels often provided inaccurate information and that less-expensive species were often swapped for sought-after fish such as Atlantic cod, red snapper and wild salmon. Oceana says each desired fish product has one or more less-expensive offerings which are common substitutions. Fish fraud is so common that Oceana says the practice undermines consumers who choose to eat specific fish for health, environmental or religious reasons. Mislabeling is common, Oceana says, because of the immediate economic incentive combined with little enforcement.

In a follow-up to its February report finding one-third of the seafood tested in the United States is mislabeled according to U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines, an oceans-protection group says Americans are paying a high price for fish fraud. Oceana, an international group advocating for protection of the world’s oceans, says that swapped species can cost consumers twice as much when cheaper counterparts are sold as premium choices. Just as horsemeat was sold as beef all over Europe when its price was only about one-fifth that of the more-expensive meat, the new report from Oceana says that seafood fraud is practiced on consumers when less-expensive and less-desirable species are passed off as high-quality fish. “Swapping a lower-cost fish for a higher-value one is like ordering a filet mignon and getting a hamburger instead,” says report author Margot Stiles. “If a consumer eats mislabeled fish even just once a week, they could be losing up to hundreds of dollars each year due to seafood fraud.” According to the Oceana study, substitution of a lower-cost species such as tilapia for more-expensive grouper could cost consumers an extra $10 for an eight-ounce filet in a restaurant, and the common substitution of Atlantic farmed salmon for wild Chinook salmon adds another $5 to a restaurant bill. Fish fraud also occurs in grocery stores when cheaper substitutes are used in place of higher-cost fish to rip off about $4 each from consumers, the study says. Oceana turned to seafood experts and about 300 menus in 12 different cities to come up with its estimates for how much fish substitutions cost consumers. “Consumers deserve to know their seafood is safe, legally caught, and honestly labeled, including information like where, when and how it was taken out of the ocean, “ Stiles said. “The more information that follows the fish, the harder it will be for fraudsters to rip off American consumers.” The 23-page Oceana report on fish fraud says part of the problem is that seafood follows a complex path “from boat to plate.” Fish often cross ocean basins and multiple countries before reaching the final point of sale. Oceana says that each stop in the supply chain is an opportunity for fraud. “Without traceability, or requiring information to follow the fish through the supply chain that is transparent and verifiable, consumers can be subject to fraud at every step the way,” the group says. Oceana supports the Safety and Fraud Enforcement for Seafood (SAFE) Act that has been pending in Congress since March. The group says it has more than 500,000 members worldwide. The fish fraud report also notes that Americans have doubled their seafood consumption in the past 50 years and that some of today’s most popular fish were not even sold in the U.S. until recent years. Freshwater Tilapia, for example, has gone from virtually unknown to the fifth most popular U.S. seafood, mostly in the past decade. Another indicator is the number of sushi bars in the U.S., which have grown five-fold in the past 10 years. More than 5,000 grocery stores also sell sushi today. In total, Americans are eating about $80 billion worth of fish annually. Oceana says 1,700 species of fish and shellfish are sold in the U.S. and that most consumers have a difficult time comparing price, quality, origin and other factors. The study found seafood labels often provided inaccurate information and that less-expensive species were often swapped for sought-after fish such as Atlantic cod, red snapper and wild salmon. Oceana says each desired fish product has one or more less-expensive offerings which are common substitutions. Fish fraud is so common that Oceana says the practice undermines consumers who choose to eat specific fish for health, environmental or religious reasons. Mislabeling is common, Oceana says, because of the immediate economic incentive combined with little enforcement.

Sponsored by Marler Clark